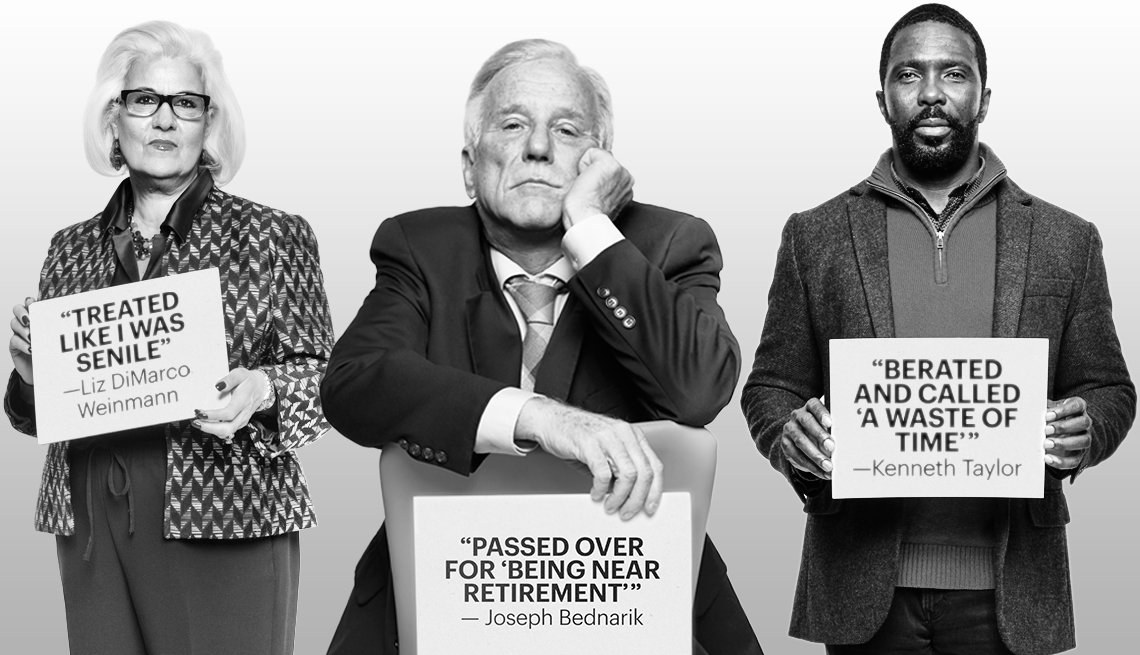

After reading Cruikshank Aronson and Dovey, I started to see how ageism shows up in so many different ways. It’s not just people making rude comments about getting older it’s in the language we use, the stories we tell, and even the way older adults start to see themselves. Each author looks at it from a different angle, but together they show how deeply ageism shapes our culture and how we treat people as they age.

The example that hit me the hardest came from Aronson’s story about her father and how his care was affected by assumptions about aging. The doctors weren’t trying to be cruel, but they treated him differently simply because of his age. That really stuck with me because it showed how bias doesn’t always look obvious it can hide behind “good intentions” or “professional judgment.” It made me think about how important it is in social work and healthcare to challenge those quiet assumptions.

Cruikshank looks more broadly at where these attitudes come from. Her section on stereotypes stood out to me, especially how older adults are often seen as frail or out of touch. That reminded me of Dovey’s take on literature, where older characters are usually written as fading away or just looking back at their youth. Both authors point out how these stories shape what we believe about aging. If all we ever see is decline, we start to believe that’s what aging has to be. It really made me think about how important representation is, we need stories that show older adults as full, capable people with their own goals and growth.

Cruikshank also talks about internalized ageism, when older adults start to believe society’s negative messages. I saw this in Aronson’s examples too patients who accepted less care or fewer options because they thought that’s what happens when you get old. Dovey shows something similar in her literary examples, where aging characters see themselves through society’s lens instead of their own. It’s a sad cycle, but it really highlights how powerful these messages can be.

Language plays a huge role in all this. Cruikshank mentions elderspeak that overly sweet or slow tone people use with older adults. Aronson talks about the “language of death” in medicine words like “frail” or “not a candidate” that quietly shut down opportunities for care. I’ve seen this happen before, and it’s made me more aware of how easily we can talk down to people without realizing it. The way we speak about older adults sends messages about how much we value them.

When Aronson says “Geriatrics is to medicine as old age is to society” it really hit me. It reminded me why I wanted to take this class to understand aging better and challenge my own biases. The hardest part for me is noticing how often those biases come up, even in small ways. Going forward I want to focus on using strengths-based language and helping clients see that aging doesn’t mean losing who they are.

Reading these authors made me realize ageism isn’t just an attitude, it’s a system that touches everything from healthcare to art. The more aware we become, the better we can push back against it in our work and in everyday life.

Mike-Anthony,

This is a really nice job on this post. You analyzed the readings, made connections and drew on your personal experiences. Well done.

Dr P