The story about Eva made the greatest impact on me because of the blatant discrimination she was receiving due to her age, which is something she can’t control. I have heard stories of rideshare drivers that have refused riders due toothier weight their concern that it would damage their vehicle or right your drivers that have refused riders with Service animals who didn’t want the hassle of having dog hair in their vehicles, but I never considered that cabs would be a place that older adults would be discriminated against. It also frustrated me because of how inconsiderate people in the service industry can be to the populations they serve. It may slow down the cab driver to take older adult riders, but they ordered the service and it’s their job to take the rider from point A to point B safely. Eva’s story also impacted me because of Eva’s strengthen and resilience in navigating the steep streets with her walker in San Francisco independently as Arsonson (2019, p. 165) reported “getting Eva out of my car and up the forty-nine stairs to her apartment ‘took nearly an hour because of her grave debility. She is very weak, has audible bone-on-bone arthritis in all major joints, frequent spasms in her left hip, minimal clearance of her right foot and could not move her left foot; I basically had to hoist her.’ I had no idea how Eva ever made it up the steps unassisted”. This example of ageism taught me how ageism really does impact everything from getting medical care to something as simple as getting a cab. Because of society’s negative attitudes towards aging, older adults are automatically at a disadvantage when navigating society as seen through the in accessibility of Eva’s apartment and the fasted paced healthcare system as they have a “mind-set that leads doctors to cut patients of all ages off after just twelve to twenty-three seconds,” (Aronson, 2019, p. 166). The only way older adults can navigate through these disadvantages is conforming to societies biases about aging or be lucky enough to have an advocate who knows the system well enough to get the older adult client the unbiased and personalized assistance they need. Aging practice isn’t just about caring for older adults’ health; it’s about caring for all aspects of the older adult’s life to improve their overall wellbeing and quality of life based on their individual needs.

Cruikshank talk about Gulliver’s travels where Gulliver encounters the Struldbrugs who “are ‘peevish, covetous, morose, vain, talkative,’ envious, impotent, incapable of friendship, ‘dead to all-natural Affection . . . and cut off from all Possibility of Pleasure.'” (Cruikshank, 2013, p. Chapter 8: Ageism, paragraph 13). The Struldbrugs are immortal but at the cost of physical and moral decay. Dovey speaks about how older adults are portrayed in media, particularly books, as “crabby, computer illiterate, grieving for his dementia-addled wife.” (Dovey, 2015, pp. 1-2). Dovery reports that part of the reason why society has such a negative connotation regarding age is due to fiction’s “standard perception of the old” (Dovey, 2015, p. 4). Both older adult characters Cruikshank and Dovey describe in their writing meet the negative biases society has put on older adults of decay, illness and instability (both physically and psychologically).

An example of internalized ageism in Aronson’s reading was Eva’s reaction of “‘That sounds too good to be true!'” (Aronson, 2019, p. 169) to Aronson’s help with getting comprehensive, supportive care due to her lowered expectations of the care she should receive. This is due to the lowered quality care and treatment she has received as an older adult and her acceptance of this social neglect and diminished treatment marked by her comment ‘It happens all the time,’ she said.” (Aronson, 2019, p. 164) when the cab she ordered sped off without her. In Dovey’s article, she identifies internalized ageism through romanticizing aging writing a story “of old age that tells a story of progress” (Dovey, 2015, p. 4). She also reported that she imagines that she would “throw off the shackles of propriety” (Dovey, 2015, p. 4) in older adulthood even though she does not currently have a rebellious attitude. Cruikshank states that “Age passing, pretending to be younger than you are, is a form of internalized ageism.” (Cruikshank, 2013, p. Chapter 8: Ageism, paragraph 66).

Chapter 8 of Cruikshank’s book focuses on Elderspeak which is “a slow rate of speaking, simple sentence structure and vocabulary, and repetitions.” (Cruikshank, 2013, p. Chapter 8: Ageism, paragraph 22). Cruikshank reports that the “Patronizing speech damages the self-esteem of elders.” (Cruikshank, 2013, p. Chapter 8: Ageism, paragraph 23) and “reinforces negative stereotypes” (Cruikshank, 2013, p. Chapter 8: Ageism, paragraph 23). Chapter 8 of Aronson book mentions “Calling an older person cute is considered infantilizing and insulting” (Aronson, 2019, p. 139). It can dimmish a person’s status as cute can be associated with being small and incompetent. Dovey’s article includes language that portrays either a generic old man who is “crabby, computer, illiterate, and grieving for his dementia-addled wife” (Dovey, 2015, p. 1) and his eccentric old women who is “radical, full of energy, a fan of wearing magenta turbans, and handing out safe-sex pamphlets outside retirement homes” (Dovey, 2015, p. 1). Using the type of language, such as “Old People Behaving Hilariously” (Dovey, 2018, p. 6) or “Old People Behaving Terrifyingly” (Dovey, 2015, p. 6) also reinforces the negative stereotypes of older adults and leads to the societal neglect and biased against older adults. I have seen some of this language used with older adults such as when someone is turning 30 or older, everyone always jokes that they will be “21 forever”. It seems very creepy and rude to me to keep insisting that someone is turning 21 year after year when getting older isn’t a bad thing. I’ve also heard guests at my restaurant job use the word “old” in a negative connotation when I ask them if they are comfortable sitting at high top tables. They usually go, “we are too old for that” but I have seen many guests older than them having no trouble sitting at the high-top tables. I always laugh it off with them as I know they say it in good fun, but I always feel the need to explain to them that I ask so I can accommodate their needs.

The issue I find most difficult and the reason I took aging practice is my interest in societies fear of aging. I find it interesting that society is so fearful and against a natural and unstoppable part of life. Society traits aging as something that is “indecent” (Dovey, 2015, p. 6) and try to deny preventing ourselves from confronting that it’s a significant part of our lives. Part of this avoidance is rooted in our language, such as “she passed away; we lost him; she’s been gone five years now; he has joined his beloved wife/daughter/parents; she is no longer with us.” (Aronson, 2019, p. 141) to avoid confronting mortality. This fear of aging also leads to ageism, which can manifest in stereotyping in media and dehumanizing older adults by stating that although adults are “just regular people who happen to be old”. (Dovey, 2015, p. 5) which dismisses the complexity of older adults. This fear can also be shown in internalized ageism where people come to accept negative society stereotypes on older adults. This can cause older adults to pretend to be younger than they are such as older adult women dying their hair to avoid the negative stereotypes of identifying as “old”. To overcome this issue, practicing a holistic and multidimensional approach would be key in treating the client as a whole person. The goal of treatment is to increase their quality of life based on their identified personal goals (Aronson, 2019, p. 145). To overcome the fear of aging, it would require having difficult conversations with clients regarding developing care plans and identifying the client’s priorities before reaching older adulthood to lessen the client’s fear, so they feel more prepared for what older adulthood entails.

Aronson, L. (2019). Elderhood: redefining aging, transforming medicine, reimagining life(1st ed.). Bloomsbury US Trade.

Cruikshank, M. (2013). Learning to be old: gender, culture, and aging (3rd ed.). Bloomsbury US Non-Trade.

Dovey, C. (2015). What Old Age is Really Like. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/what-old-age-is-really-like

I agree with you that we need more choices for navigating some of the disadvantages of aging in a system that does not recognize the needs of elders. It shouldn’t be a choice between internalized ageism and luck of advocacy. I like your example of Eva’s internalized ageism in not expecting better treatment because she has not received it or been listened to in her later life. I also find it interesting that society is so fearful of something that everyone, if they live long enough, will experience.

Your point about how society’s attitudes shape services and expectations really stood out, especially when Eva seemed surprised to receive proper support because she had gotten so used to being dismissed. I also agree with your connection between stereotypes in media and internalized ageism; when older adults constantly see themselves portrayed as weak, “cute,” or incapable, it’s no surprise they begin to accept lower standards of treatment. The language examples you gave, like joking about being “too old” or calling people “21 forever,” really highlight how normalized ageist comments have become, even when they seem harmless. I think your focus on society’s fear of aging is insightful, and your emphasis on holistic, person-centered care shows a thoughtful approach to countering ageism in practice.

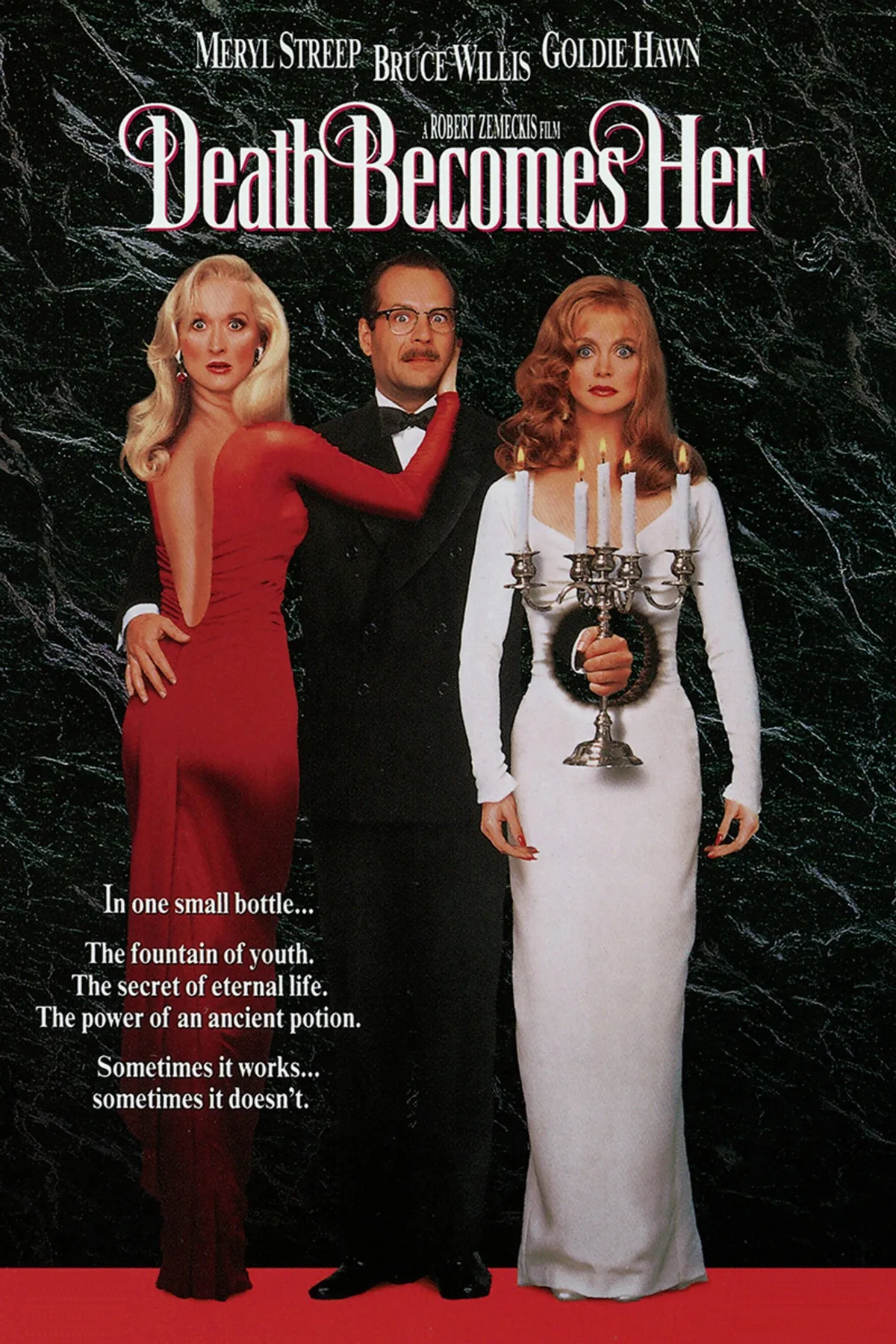

Another great movie! I loved that you referenced “Death Becomes Her”, it is such a clever but deeply dark comedic look at society’s obsession with youth. The movie perfectly captures society’s obsession with youth and beauty, showing how far people will go to avoid the visible signs of aging. Both main characters literally destroy themselves in pursuit of eternal youth, which mirrors the internalized ageism we’ve discussed, the belief that aging equates to loss of worth or desirability. The film exaggerates this to the extreme, but it highlights a very real cultural message: that women, in particular, are valued for how young they look rather than for their wisdom or experience. Your post really made me think about how entertainment both reflects and reinforces these harmful idals about aging. I hope everyone in the class gets a chance to view this film.

I’ve loved “Death Becomes Her” since I was a child. You chose well. I’m a little jealous that I didn’t think of it 🙂

I’m happy you brought up Eva’s story. I was shocked that she said it was common for cabs to speed away and avoid her because of her physical limitations. I know that people are frequently the victims of discrimination based on their race in this context. I’m ashamed to say that had never even occurred to me. I know what Aronson shares is anecdotal; a story, not statistics– but I would be willing to believe that it is commonplace for older adults and people with disabilities. Access and affordability are often the facilitators/barriers when we talk about transportation, but rarely is ageism or ableism part of the conversation.

Gianna,

Really good post. Nice job and I enjoyed reading it.

Dr P