Turning forty this year brought a mix of humor and humility for me. I recently found out I need my gallbladder removed, despite losing weight and having perfect blood work, while my husband was diagnosed with gout. We laughed and shrugged it off with, “I guess this is what happens when you get old.” That simple statement stuck with me, revealing how deeply internalized ageism is, even for someone aware of these biases. Without thinking, we immediately linked minor health changes to “getting old,” as if aging itself is inherently negative. This moment highlighted for me how ingrained and automatic these ageist assumptions are, and how important it is as a future social worker to challenge these narratives in practice.

Both Cruikshank (2013) and Dovey (2015) illustrate how aging is often framed through narrow stereotypes. Cruikshank notes that English cartoons repeatedly depicted older adults with failing eyesight, failing memory, or reduced sexual activity. Similarly, Dovey observes that authors imagining older characters default to hearing loss, arthritis, slowing, and loss of balance, assuming these are inevitable hallmarks of aging. These stereotypes present aging as a stage of loss rather than a period of possibility, growth, and complexity. Recognizing these patterns in literature reinforced for me the importance of viewing older adults as multidimensional and varied, rather than through simplified cultural lenses.

Internalized ageism emerges when individuals unconsciously absorb societal messages about aging. Dovey (2015) writes about creating a “spunky, elderly female character” and realizing she had romanticized old age as a story of progress, projecting narrow cultural expectations onto herself. This reflects internalized ageism: she unconsciously accepted that aging should mean either decline or exceptional vitality, rather than ordinary complexity. Aronson (2019) provides another example of internalized ageism in her personal struggle with gray hair. Despite being a geriatrician and an advocate for aging, she spent decades dyeing her hair back to its “original” dark brown to avoid looking “old.” Even after turning fifty, when she acknowledged that “all fifty-year-olds have gray hair,” she still perceived the contrast between “old” gray and “young” brown as unattractive. This reflects her internalized ageism around the transition to older adulthood. Just as she resisted the visual signs of aging in her hair, she grappled with societal expectations of what it means to age, feeling pressure to maintain a youthful appearance despite her professional commitment to embracing elderhood. Both examples illustrate how pervasive societal expectations of age can influence personal choices and self-perception, even among those knowledgeable about aging.

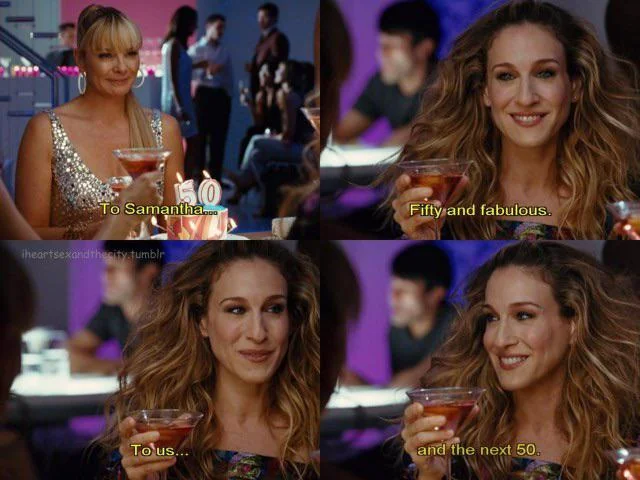

Language plays a key role in perpetuating ageism. Aronson (2019) highlights how older adults are often portrayed as so “incapacitated that ordinary activities become extraordinary”. This reminded me of the Sex and the City example, where Samantha turns fifty and is celebrated as “Fifty and Fabulous.” While seemingly empowering, the phrase frames aging as an exception rather than a norm, implying that confidence and vitality are remarkable only for older adults. While the show’s characters worshiped the magazine “The New Yorker”, I found interesting to pull a similar use of language by Dovey. Dovey (2015) notes the language of caricature, from “the smiling old dear to the grumbling curmudgeon,” reducing older adults to simplistic stereotypes and ignoring the richness and diversity of their experiences. Ultimately, both Aronson and Dovey show that the words we use matter: language can either reinforce ageist assumptions or help challenge them by acknowledging the richness, diversity, and continued potential of older adulthood.

I took this class because, while I was aware of the statistics about the aging population and knew this group required attention, I realized I didn’t know much about aging beyond what I had seen in rehab facilities. My prior experience mostly exposed me to elders in states of illness or recovery, which shaped a limited view of aging. Through these readings, I’ve been confronted with my own deeply ingrained ageism and have recognized how easily I internalize societal assumptions about what it means to get older. The issue I find most difficult is confronting these biases, both in myself and in societal structures that undervalue older adults, because they are so deeply embedded and often go unquestioned. In my practice, I plan to address this by actively reflecting on my assumptions, challenging stereotypes, educating clients and families about the diversity of aging experiences, and modeling acceptance of aging as a natural, valuable stage of life.

References

Aronson, L. (2019). Elderhood: Redefining aging, transforming medicine, reimagining life (1st ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing.

Cruikshank, M. (2013). Learning to be old: Gender, culture, and aging (3rd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield.

Dovey, C. (2015, October 1). What old age is really like. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/what-old-age-is-really-like

It’s interesting how quickly we attribute physical and psychological health changes to aging. It remind me how even people who actively challenged their types can still have internalized them without realizing it. I also like how you connected Aronson’s experience with dying her hair to society’s pressure to look youthful. Like the readings described, it’s something that has been instilled into us since childhood through media and society when our parents told us to stop making silly faces or squinting because it would cause wrinkles. I agree with your point about language as “fifty and fabulous” may sound empowering on the surface, but subtly imply that it’s unusual for older adults to be confident and lively. Your plan to combat the stereotypes by reflecting on your assumptions and being intentional about the language, you use of clients and colleagues is a great step in shaping societies stereotype views on older adulthood.

Happy 40th! The enlightenment that has come as a result of being a student in this course has been paramount for me as well! There have been several under the radar philosophies that I have housed and nurtured about the aging process. But, specifically older adult age and, what I deemed to be, the automatic disadvantages and shortcomings as a result of that blessing of growing older. It is interesting to take apart those phrases intended to celebrate getting older because they do have a protesting element to them. It does seem to have the intention of disassociation to the doty and popular narrative of aging and replace it with one filled with optimism and hope!

Your example of linking health changes to getting old and seeing that as an inevitability is interesting. I have done that myself. I agree that we need more stories of old age portrayed in a more multi-faceted way. I’m glad that there are more older writers writing about their experiences so that we can get a more realistic view of this time of life, free of the stereotypes that we project onto a sizeable segment of the population. I really like what you said here: “she unconsciously accepted that aging should mean either decline or exceptional vitality, rather than ordinary complexity.” We expect people to either be exceptional or decrepit but it is a much broader spectrum of experience. I agree that the biases are deeply embedded and we are conditioned to accept them unquestioningly.

Welcome to the 40 Club! This is a testament of how ageism can infiltrate our everyday conversations, even among those who strive to be aware of these biases. The way you and your husband shrugged off health concerns with a casual with a casual “this is what happens when you get old” highlights how ingrained these assumptions can be. It’s important to challenge these narratives, not just for yourself but for those you will work with as well.

I like the way you gave a more simplistic portrayal of Cruikshank and Dovey’s critiques of aging in media and literature. The framing of aging as mainly a time of loss does a disservice to the richness and complexity of older adulthood. Your self-awareness about your own biases and the limited views shaped by previous experiences in rehab facilities is impressive. I think you can further enrich your understanding by engaging more closely with older adults in your community to hear their stories and perspectives directly. I know this would give you an eye opening experience. Great Post!

Your reflection on turning forty adds a genuine and relatable layer to this discussion. I appreciate how you connected your personal experience with the academic insights from Cruikshank, Dovey, and Aronson. Your example about casually linking minor health issues to “getting old” perfectly illustrates how internalized ageism can appear in everyday language. I also appreciated how you connected this awareness to your future social work practice by emphasizing the importance of reflection and advocacy. Recognizing ageism within ourselves is a critical first step toward challenging it in society. Your post shows strong self-awareness and commitment to ethical, culturally competent practice.

Congrats on your 40th!! Great post as well. It’s important to note that you and your partner tried to joke about getting older. It’s common to think of it as usual, and many people blame most health issues on getting old. I also liked the example you chose to talk about, mainly because im a big sex and the City fan! The way they all talk about aging impresses me because, even though sometimes it seems like everyone at that age should have it all figured out.

Kacey,

This post was excellent and very well written. I appreciate your sharing your own experiences and relating them to what we have been discussing. I enjoyed reading it. Thank you.

Dr P